Wearing caste on the wrist — green for Dalits, red for Thevars

Last month, a 12-year-old Dalit boy in Jodhpur was beaten up by his teacher for allegedly taking a plate from a stack meant for upper castes. The Indian Express visits schools across the country where lessons in caste differences start early.

Written by Arun Janardhanan | Chennai |Share on facebooShare on twitterShare on google_plusone_share

Sivakani , a 15-year-old from Gopalasamudram, had to quit studies after the Dalit school in her village shut down and her parents couldn’t afford to send her elsewhere. (Express Photo by: Arun Janardhanan)

Sivakani , a 15-year-old from Gopalasamudram, had to quit studies after the Dalit school in her village shut down and her parents couldn’t afford to send her elsewhere. (Express Photo by: Arun Janardhanan)

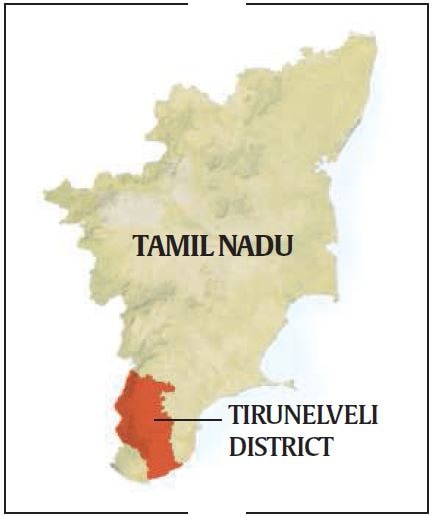

IN the schools of Tirunelveli, about 650 km south of Chennai, caste comes in shades of red, yellow, green and saffron. It’s what students wear on their wrists, on their foreheads, around their necks, under their shirts. It’s who they are.

At the Government Higher Secondary School in Tirunelveli town, a Class X student extends his hand to display his green-and-red kayaru, a wrist band of interwoven threads. “The upper castes have yellow-red bands, so we have these,” he said.

In this belt in southern Tamil Nadu known for violent caste conflicts between OBCs and Dalits, these wrist bands are markers that tell children who is a friend, who isn’t. Though there are no written rules, students usually know their ‘colours’ by the time they reach high school.

It’s red and yellow for Thevars, blue and yellow for Nadars, saffron for Yadavs — all socially and politically powerful Hindu communities that come under the Most Backward Classes (MBC) category — while students of the Dalit community of Pallars wear wrist bands in green and red and the Arundhathiyars, also Dalits, wear green, black and white.

In August, while investigating the increasing number of clashes between student groups, the district administration found that wrist bands were often used to target on the basis of caste. The district collector then asked the education department to ban wrist bands in schools in Tirunelveli. There was no written order, only a direction issued at a meeting of the education department. A headmaster, who was present at the meeting, said, “It was a verbal direction but a strong one,” he said.

Chief Educational Officer of Tirunelveli R Swaminathan confirmed that they had issued such a warning. “We have already directed all schools to ban such bands following reports of caste clashes based on colour. Not just wrist bands, any colour that they use to identify their caste is banned,” he said.

Chief Educational Officer of Tirunelveli R Swaminathan confirmed that they had issued such a warning. “We have already directed all schools to ban such bands following reports of caste clashes based on colour. Not just wrist bands, any colour that they use to identify their caste is banned,” he said.

But it’s easier said than done. These kaiyarus can be confused for sacred threads handed out in temples and it’s hard to impose any such ban. Besides, there are more ways to talk caste.

A Dalit student of a school in Tirunelveli town said the pottu (bindi or tilak) worn by students were also colour-coded. “If you wear a pottu with yellow sandalwood paste, with a dash of vermilion on it, I know you are a Thevar,” he said. The other dominant castes, like the Nadars, have their own colour-coded tilaks; Dalits, he said, usually don’t wear them.

The 13-year-old likes yellow — “it’s my favourite colour” — but he can’t wear it because he will be “questioned” by the Thevars. “We get a yellow kayaru from temples, but I can’t wear that on my wrist. If I did, they would taunt me and call it a ‘rowdy band’,” said the Class X student.

He says he can’t risk the wrath of the upper-caste students because he is new to this school. This year, he moved to Tirunelveli town from the Dalits-only school in Gopalasamudram village. The school in his village was once part of the Pannai Venkatramaiyer High School, but in November 2013, after a caste tension in the village, a separate branch was set up for Dalits and he was among the 140 students who moved there. But in June this year, the district administration refused to renew permission for the Dalits-only school, forcing most of the students to drop out. One of the students, 15-year-old Sivakani, was forced to quit studies as her parents couldn’t afford to send her to a school outside the village.

C Lakshmanan, an assistant professor of the Madras Institute of Development Studies and a leading researcher of Dalit issues, said such practices in Tamil Nadu could be attributed to the lack of political representation for Dalits. While the Scheduled Castes make up 20 per cent of the population in the state, they have poor political representation.

“These practices emerged in the 1990s. When we were working to implement the Panchayati Raj Act in the state, we came across a series of instances of Dalits being barred from local body elections. Around the same time, political movements representing OBCs also began to take shape, giving these OBC communities better social clout. So while these dominant communities used markers such as wrist bands to single out and subjugate Dalits, for the Dalits, these were ways of asserting themselves,” he said.

A headmaster at a school near Tirunelveli town said there were other markers. “Like you have different houses — green house, yellow house, etc — in city schools, children here wear coloured vests. We cannot ban everything, definitely not what children wear under their uniform. These vests come in handy during a game of basketball to draw up teams based on caste lines, but they are as effective to settle scores,” said

The headmaster said anything, even a song, can trigger caste tension among students. Recalling one such instance, he said, “Recently, a Dalit student on a bus played a song on his cellphone hailing Ambedkar. A Thevar student responded by playing a song in praise of his caste from the Kamal Hasan movie, Thevar Magan. This led to a clash between students representing both communities,” he said.

Students also wear lockets with photographs of leaders representing their castes. K Kamaraj lockets are popular among Nadar students; the Thevars wear lockets with photographs of U Muthuramalingam Thevar, a veteran political leader for Thevars; the Yadavs have claimed Veeran Alagumuthu Kone, one of the first freedom fighters, as their own; while in Coimbatore and Namakkal regions of the state, Gounder students wear lockets of Dheeran Chinnamalai, one of the commanders in the Polygar Wars of 1801-1802.

People here say such caste markers were unheard of until two decades ago. “These practices coincided with the rise of several caste-based political parties (such as the Samathuva Makkal Katchi of Nadars and the All India Moovendar Munnani Kazhagam of Thevars) and movements. While such practices are particularly visible in Tirunelveli, you will find them across the state,” said M Bharathan of the Human Rights Council based in Tirunelveli.

“Wrist bands and coloured vests are just what you see. There’s much more to this conflict,” said Lakshmanan. Tirunelveli district collector M Karunakaran said he ordered the ban on coloured wrist bands and other things used to identify caste following a police report on the increasing number of caste-based clashes in schools. “We banned all sorts of things, including wrist bands, after a police report studied the pattern of violence in schools and colleges. The police sought help from the district administration. Not only schools, college officials too were called for a meeting where we asked them to ban such things,” he said.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed Twitter

Twitter

0 comments:

Post a Comment